| Login | ||

Healthcare Training Institute - Quality Education since 1979

CE for Psychologist, Social Worker, Counselor, & MFT!!

Section

3

Triggers in PTSD

Question

3 | Test

| Table of Contents

Read content below or listen to audio.

Left click audio track to Listen; Right click to "Save..." mp3

In the last section, we discussed survivor guilt and other self-destructive behaviors arising from PTSD such as: self-mutilation, substance addiction, and eating disorders.

In this section, we will examine the effects of triggers

on PTSD clients and also various types of triggers, for example, anniversary

triggers, current stresses, and bodily triggers. We will discuss these

from the perspective of combat and natural disasters.

PTSD Triggers

♦ #1 Anniversary Triggers

The first type of trigger is an anniversary reaction. Obviously,

these triggers include anniversary dates that remind a client of the trauma.

Grant had survived a bloody battle in Iraq against insurgents in May and June. Around

these months every year, Grant reports feeling nervous, anxious, and nauseous. When

he first came to me, he stated, "I don’t know why these months

are so bad for me. I think its allergies or something."

I

asked Grant if he could check the records regarding his time in Iraq. He

said yes, and the next session I had with him, Grant stated to me, "Hey,

Doc. You won’t believe this! You know how

I said I get real sick every May 19th? Well, that’s the day the

insurgents sent an IED, oh that’s an improvised explosive device, straight

into our Stryker IVC."

Although I was not as surprised as he thought

I would be, Grant found it helpful to know from where his

reactions were stemming. Rather, his body was reacting to the dates during which he experienced trauma.

♦ #2 Current Stresses

The second type of trigger is current stresses. It is

common for the slightest amount of current stress to augment PTSD symptoms

including trigger symptoms. Grant became irritated when he began to have

increased symptoms during months in which no combat took place. Grant

stated, "Nothing happened to me in the war during these months. So

why am I seeing my dead buddies in the room with me all week? I thought

you said I wasn’t crazy."

This time, his triggers had been

unrelated to any specific dates, so I asked him if he had been under any stress

during the week. Grant responded, "My wife lost her job,

and we’ve been having money troubles all month." I explained

to Grant that this extra stress could be what triggered his symptoms this time,

not the dates.

Think of your PTSD client. Do they have an increase

in symptoms even though there is no visible trigger about? Could they

be suffering from current stresses? If so the Trigger Chart described later

in this section may be beneficial.

♦ #3 Other Reminders

In addition to anniversary triggers and current stresses, a third type

of trigger is a bodily trigger. Bodily triggers are those that relate

to the senses.

For instance, the sight of red may

trigger the memory of blood in a veteran’s mind or the backfiring of

a car could trigger a memory of gunshot. Such things as news stories

related to a client’s trauma or even talking to other

people may also trigger a client’s PTSD symptoms.

As you know

bodily triggers include the following:

- Visual

- Auditory

- Olfactory or smell

- Taste

- Physical. This can relate to the sensation of movement, touch, or pain.

Do you need to think of body triggers as a criteria for your next session or play this section during your next session for the client?

Leo, a PTSD client had been in his camper when a tornado ripped through it. As a result of his injuries, the doctors were forced to amputate his leg. Just before the tornado hit, Leo had been cooking pasta in his camper’s kitchen. Now, whenever he smells cooking pasta, Leo begins to feel sick to his stomach, and has to fight a great urge to flee to a basement or windowless room. As you can see, Leo is suffering from an olfactory trigger.

♦ Technique: Trigger Chart

To help my PTSD clients like Grant and Leo identify their triggers more successfully,

I suggested they make a "Trigger Chart." You

might consider trying this technique with those PTSD clients who have trouble

identifying triggers and anticipating triggers in their environment. I

asked Leo and Grant to divide a piece of paper into three sections, each

column labeled: "trigger," "my reactions,"

and "traumatic memory."

Under the trigger column, I asked

them to write certain dates, objects, or stressors that cause their PTSD

symptoms to intensify. Under the "my reactions" column,

I asked them to list specific emotions and thoughts that

occur when they come into contact with a trigger. Finally, under "traumatic

memory," I asked them to write a memory of the trauma

that could somehow be linked to the trigger.

Grant, the war vet... wrote

under "trigger," "Someone, an authority figure, tells

me to do something in a disrespectful, rough, or impersonal tone of voice." Under "my

reactions," Grant wrote, "Anger, desire to fight

back, desire to run away instead of hitting the person or having to hide

my rage." Finally, under "traumatic memory," Grant

wrote, "It reminds me of the CO who sent my buddy on a worthless, dangerous

mission that got my buddy killed so that he could look good."

After Grant completed this part of the exercise, I asked

him to divide this and any other triggers he had into four categories:

(1) triggers he felt might be the easiest to endure;

(2) triggers he felt he

might be able to handle after a few more months of healing;

(3) triggers

he felt he might be able to confront in a few years; and

(4) triggers he

planned to avoid for the rest of his life.

For those triggers he felt

he could handle easiest, Grant wrote, "hearing a car backfire, seeing bright flashes." For

those triggers that Grant felt he might be able to handle after

a few more months of healing, he wrote, "watching

a movie with explosions in it."

For those triggers he felt he might

be able to confront in a few more years, Grant wrote, "dealing

with other stresses in my life." And those triggers that Grant

felt he could never healthfully confront were, "anniversary

dates." Now that Grant has prioritized his triggers,

he can more effectively face them without being overwhelmed by confronting

them all at once.

Client Exercise: Identifying Triggers

At this point you will make a trigger chart, which can be invaluable to you first in identifying, and later in anticipating, situations in which you might react as if the trauma were recurring.

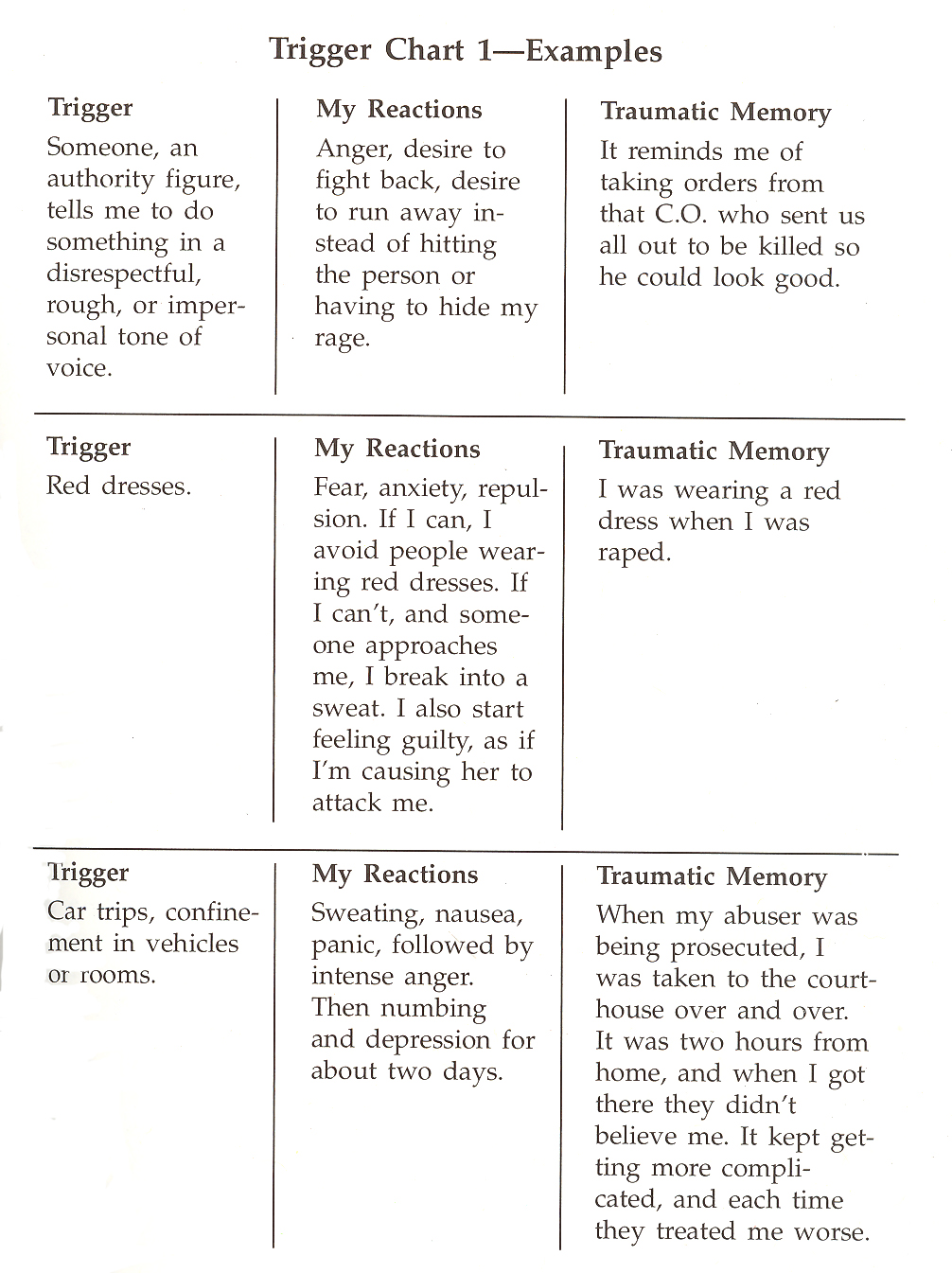

Give a piece of your journal paper the heading "Trigger Chart 1" and draw three columns. Label the first column "Trigger," the second "My Reactions," and the third "Traumatic Memory."

In the first column list those times or instances when you feel the adrenaline rush to fight or run, or where you shut down or go numb, emotionally, physically, or both. Examples of triggers include smells, sights, sounds, people, or objects that remind you of the trauma or of events associated with the trauma.

Triggers might also include current stresses, such as the following: • Interpersonal difficulties at home or at work • Any kind of work or emotional overload • Financial or medical problems (including premenstrual syndrome) • Increased crime or other neighborhood problems • Witnessing or being involved in a current trauma (a fire, car accident, natural catastrophe, crime, etc.)

In the second column, indicate your reactions to each trigger situation. Your reactions in each situation will not necessarily be the same. Possible responses include • Anger or rage • Isolating yourself or overworking • Self-condemnation • Increased cravings for food, alcohol, or drugs

• Increased flashbacks • Self-mutilation • Depression • Self-hatred • Suicidal or homicidal thoughts • Increased physical pain (headaches, backaches) • Activation of a chronic medical condition (increased blood sugar if you are diabetic, increased blood pressure if you suffer from hypertension, recurrence of urinary tract infections if you are prone to bladder problems, etc.)

In the third column, try to trace the trigger to the original traumatic event, to a secondary wounding experience, or to an event associated with these experiences. If you cannot remember the original events, do not be overly concerned. The main point of completing this chart is to help you to understand and anticipate when you might be triggered. This understanding is the first step toward change and toward control.

Take a look at the Trigger Chart 1 examples to get an idea of how it works. Consider sharing your chart with your family members and friends. They might be able to help you add instances to your trigger list. Also, sharing this chart will help them to understand you better and ease any stresses in your relationship.

- Matsakis PhD, Aphrodite; I Can’t Get Over It: A Handbook for Trauma Survivors; New Harbinger Publications, Inc: California; 1992

Personal

Reflection Exercise #4

The preceding section contained information

about constructing a Trigger Chart. Write

three case study examples regarding how you might use the content of this section

in your practice.

Reviewed 2023

Update

Enhancing exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD): a randomized clinical trial of virtual reality and imaginal

exposure with a cognitive enhancer

- Difede, J., Rothbaum, B. O., Rizzo, A. A., Wyka, K., Spielman, L., Reist, C., Roy, M. J., Jovanovic, T., Norrholm, S. D., Cukor, J., Olden, M., Glatt, C. E., & Lee, F. S. (2022). Enhancing exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a randomized clinical trial of virtual reality and imaginal exposure with a cognitive enhancer. Translational psychiatry, 12(1), 299. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02066-x

In this section, we discussed the effects of triggers on

PTSD clients and various types of triggers: anniversary triggers, current

stresses, and bodily triggers.

Reviewed 2023

Peer-Reviewed Journal Article References:

Boysen, G. A. (2017). Evidence-based answers to questions about trigger warnings for clinically-based distress: A review for teachers. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 3(2), 163–177.

Boysen, G. A., & Prieto, L. R. (2018). Trigger warnings in psychology: Psychology teachers’ perspectives and practices. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 4(1), 16–26.

Captari, L. E., Riggs, S. A., & Stephen, K. (2021). Attachment processes following traumatic loss: A mediation model examining identity distress, shattered assumptions, prolonged grief, and posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(1), 94–103.

Chang, C., Kaczkurkin, A. N., McLean, C. P., & Foa, E. B. (2018). Emotion regulation is associated with PTSD and depression among female adolescent survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(3), 319–326.

Lehmann, C., & Steele, E. (2020). Going beyond positive and negative: Clarifying relationships of specific religious coping styles with posttraumatic outcomes. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12(3), 345–355.

Lehrner, A., & Yehuda, R. (2018). Trauma across generations and paths to adaptation and resilience. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(1), 22–29.

Macdonald, A., Pukay-Martin, N. D., Wagner, A. C., Fredman, S. J., & Monson, C. M. (2016). Cognitive–behavioral conjoint therapy for PTSD improves various PTSD symptoms and trauma-related cognitions: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 157–162.

Marshall, A. D., Roettger, M. E., Mattern, A. C., Feinberg, M. E., & Jones, D. E. (2018). Trauma exposure and aggression toward partners and children: Contextual influences of fear and anger. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(6), 710–721.

QUESTION

3

What are the three types of triggers?

To select and enter your answer go to Test.