| Login | ||

Healthcare Training Institute - Quality Education since 1979

CE for Psychologist, Social Worker, Counselor, & MFT!!

Section 6

A Paradigm of Crisis Intervention with a Chronic Psychiatric Client

Question 6 | Answer Booklet | Table of Contents

According to Caplan (1964:40), there are four developmental phases in a crisis:

1. There is an initial rise in tension as habitual problem-solving techniques are tried,

2. There is a lack of success in coping as the stimulus continues and more discomfort is felt.

3. A further increase in tension acts as a powerful internal stimulus and mobilizes internal and external resources. In this stage emergency problem-solving mechanisms are tried. The problem may be redefined or there may be resignation and the giving up of certain aspects of the goal as unattainable.

4. If the problem continues and can neither be solved or avoided, tension increases and a major disorganization occurs.

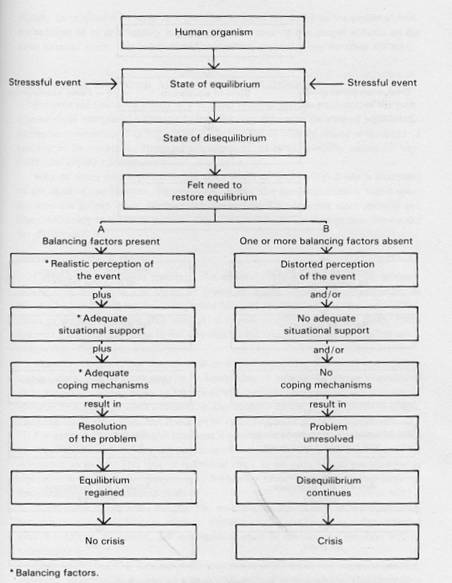

Whenever a stressful event occurs, there are certain recognized balancing factors that can effect a return to equilibrium; these are perception of the event, available situational supports, and coping mechanisms as shown in Fig. 1. The upper portion of the paradigm illustrates the "normal" initial reaction of an individual to a stressful event. A stressful event is seldom so clearly defined that its source can be determined immediately. Internalized changes occur at the same time as the externally provoked F stress, and as a result, some events may cause a strong emotional response in one person, yet leave another apparently unaffected. Much is determined by the presence or absence of factors that can effect a return to equilibrium. In column A of Fig. 1 the balancing factors are operating and crisis is avoided. However, in column B the absence of one or more of these balancing factors may block resolution of the problem, thus increasing disequilibrium and precipitating crisis.

Chronic Psychiatric Patient—theoretical concepts

Crisis intervention has gained recognition as a viable therapy modality to assist individuals through acute traumatic life situations. As large psychiatric facilities, slowly or rapidly according to individual state laws, are beginning to shorten the length of hospitalization, the chronic psychiatric patient is returning to his community where continuity of care must be maintained. The questions to be asked and answered are:

(1) Does crisis intervention work successfully with chronic psychiatric patients?

(2) If not, what other methods must be used to keep this patient functioning in his community?

With a chronic psychiatric patient as with any patient, identification of the precipitating event, the symptoms the patient is exhibiting, his perception of the event, his available situational supports, and his usual coping mechanisms are crucial factors in resolving his crisis.

Situational supports are those persons in the environment whom the therapist can find to lend support to the individual. A patient may be living with his family or friends; are they concerned enough—and do they care enough—to give him help? The patient’s situational supports can serve as "assistants" to the therapist and the patient. They are with him daily and are encouraged to have frequent communication with the therapist. Usually situational supports are included in some part of the therapy sessions. This provides them with the knowledge and information they need to help the "identified" patient. If the patient is living in a board-and-care facility, one must determine if any of its members are concerned and willing to work with the therapist to help the individual through the stressful period. This involves visits to the facility and conducting collateral or group therapy with the patient and other members to get and keep them involved in helping to resolve the crisis.

Occasionally the patient has no situational supports. He may be a social isolate; he may have no family and may have acquaintances but no real friends with whom he can talk about his problems. Usually an individual such as this has many difficulties in interpersonal relationships at work and school and socially. It is then the therapist’s role to provide situational support while the patient is in therapy.

Our experiences have verified for us that crisis intervention can be an effective therapy modality with chronic psychiatric patients. If a psychiatric patient with a history of repeated hospitalizations returns to the community and his family, his reentry creates many stresses. While much has been accomplished to remove the stigma of mental illness, people are still wary and hypervigilant when they learn that a "former mental patient" has returned home to his community. In his absence the family and community have, consciously or unconsciously, eliminated him from their usual life patterns and activities. They then have to readjust to his presence and include him in activities and decision making. If for any reason he does not conform to their expectations, they want him removed so that they can continue their lives without his possible disruptive behavior.

The first area to explore is to determine who is in crisis: the patient or his family. In many cases the family is overreacting because of its anxiety and is seeking some means of getting the "identified" patient back into the hospital. The patient is usually brought to the center by a family member because his original maladaptive symptoms have begun to reemerge. Questioning the patient or his family about medication he received from the hospital and determining if he is taking it as prescribed are essential. If the patient is unable to communicate with the therapist about what has happened or what has changed in his life, the family is questioned as to what might have precipitated his return to his former psychotic behavior. There is usually a cause-and-effect relationship between a change, or anticipated change, in the routine patterns of life-style or family constellation and the beginnings of abnormal overt behavior in the identified patient. Often families forget or ignore telling a former psychiatric patient when they are contemplating a change because "he wouldn’t understand." Such changes could include moving or changing jobs. This is perceived by the patient as exclusion or rejection by the family and creates stress that he is unable to cope with; thus he retreats to his previous psychotic behavior. Such cases are frequent and can be dealt with through the theoretical framework of crisis intervention methodology.

Rubinstein (1972) stated that family-focused crisis intervention usually brings about the resolution of the patient’s crisis without resorting to hospitalization. In a later article in 1974, he advocated that family crisis intervention can also be viable alternative to rehospitalization. Here the emphasis is placed on the period immediately after the patient’s release from the hospital. He suggested that conjoint family therapy begin in the hospital before the patient’s release and then continue in an outpatient clinic after his release. His approach has also served to develop the concept that a family can and should share responsibility for the patient’s treatment.

In Decker’s 1972 study, two groups of young adults were followed for 2-12 years after their first psychiatric hospitalization. The first group was immediately hospitalized and received traditional modes of treatment, and the second group was hospitalized after the institution of a crisis intervention program. The results of the study indicated that crisis intervention reduced long term hospital dependency without producing alternate forms of psychological or social dependency and also reduced the number of rehospitalizations.

Crisis Interventions for People with Severe Mental Illnesses

- Murphy, S., Irving, C. B., Adams, C. E., and Driver, R. (2012). Crisis Interventions for People with Severe Mental Illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev., 5. p. 1-73. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001087.pub4

Personal

Reflection Exercise Explanation

The

Goal of this Home Study Course is to create a learning experience that enhances

your clinical skills. We encourage you to discuss the Personal Reflection

Journaling Activities, found at the end of each Section, with your colleagues.

Thus, you are provided with an opportunity for a Group Discussion experience.

Case Study examples might include: family background, socio-economic status, education,

occupation, social/emotional issues, legal/financial issues, death/dying/health,

home management, parenting, etc. as you deem appropriate. A Case Study is to be

approximately 225 words in length. However, since the content of these “Personal

Reflection” Journaling Exercises is intended for your future reference, they

may contain confidential information and are to be applied as a “work in

progress.” You will not

be required to provide us with these Journaling Activities.

Personal

Reflection Exercise #1

The preceding section contained information about a paradigm of crisis intervention with a chronic psychiatric client. Write three

case study examples regarding how you might use the content of this section in

your practice.

Update

Crisis Intervention

Wang, D., & Gupta, V. (2023). Crisis Intervention. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Peer-Reviewed Journal Article References:

Bhuptani, P. H., & Messman, T. L. (2021). Role of blame and rape-related shame in distress among rape victims. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

Dutton, M. A., Dahlgren, S., Martinez, M., & Mete, M. (2021). The holistic healing arts retreat: An intensive, experiential intervention for survivors of interpersonal trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

Gilbar, O., Wester, S. R., & Ben-Porat, A. (Apr 30, 2020). The effects of gender role conflict restricted emotionality on the association between exposure to trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate partner violence severity. Psychology of Men & Masculinities.

Hill, N. T. M. (2020). Review of Reducing the toll of suicide: Resources for communities, groups, and individuals [Review of the book Reducing the toll of suicide: Resources for communities, groups, and individuals, by D. De Leo & V. Poštuvan, Eds.]. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention.

QUESTION 6

According to Aguilera, what are five crucial factors in resolving a crisis with a client with chronic psychiatric concerns? To select and enter your answer go to Answer

Booklet.