| Login | ||

Healthcare Training Institute - Quality Education since 1979

CE for Psychologist, Social Worker, Counselor, & MFT!!

Section 6

Helping Caregivers Differentiate Between

Preparatory Grief and Depression

Question 6 | Test | Table of Contents

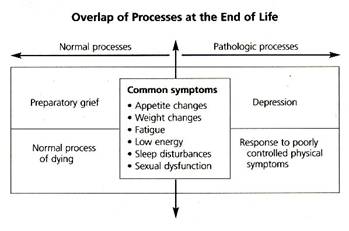

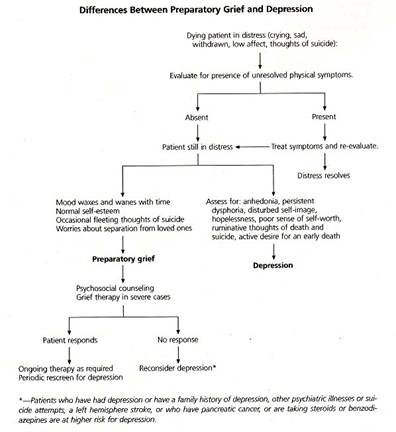

Because many of the traditional signs of depression are also present in patients who are grieving, it can be challenging to separate the relative contribution of depression and grief in patients' presentations. The following questions can be used to explore a patient's moods. Do you feel depressed most of the time? Do you feel that you are better off than many other people in similar situations?

Some patients and their families will be readily able to identify depression. Others, however, may not be able to differentiate possible depression from grief or the normal changes that occur in the dying process.

The following points highlight differences between preparatory grief and depression.

Temporal Variation. Grief is often experienced in waves, which are usually triggered in response to a specific loss. New waves of grief may be "predictably" triggered in response to a new loss (e.g., when an ambulatory patient becomes bedridden), or "unpredictably" triggered by seemingly minor incidents (e.g., hearing a treasured song or noticing a stranger's resemblance to a loved one). In contrast, persistent flat affect or dysphoria that pervades all aspects of patients' lives is characteristic of depression.

Progress with Time. In most cases, patients progress through grief and it slowly diminishes in intensity over time. Patients may periodically experience intense waves of grief (an acute grief reaction), but the overall intensity wanes.

Depression is a pathologic state. Patients can "get stuck" in this state without treatment.

Negative Self-Image. Patients who are grieving usually have a normal self-image. Some patients may have a loss of self-esteem because of the debilitation and dependency caused by progressing disease. When these feelings are disproportionate to a patient's situation, underlying depression should be considered. Patients who are depressed may have a sense of worthlessness and disturbed self-esteem.

Anhedonia. The ability to feel pleasure is not lost in persons who are grieving. Most will still look forward to special occasions and visits from family and friends. Anhedonia is a clue to clinical depression.

Hopelessness. A person who is grieving maintains a sense of hope. Hope may shift, for example, from the hope for a cure to the hope for prolonging life to the hope to live comfortably and well for the duration of life, but it is not lost in persons who are dying. Pervasive hopelessness, however, is a hallmark of depression.

Response to Support. Patients who are grieving often need social interaction to help them through the grieving process. Social support enables patients to tolerate the pain of loss while providing the necessary assistance for completion of grief work. Patients may withdraw socially during the grief process, but this withdrawal is usually a temporary pause for reflection. When patients have processed their acute grief, they usually slowly reenter society. Social withdrawal can be a manifestation of untreated physical symptoms such as pain. In advanced stages of dying, social withdrawal can also naturally occur when the person who is dying begins to let go of social attachments. Patients who are depressed often do not derive pleasure or solace from social interaction and may appear isolated and withdrawn. While temporary social withdrawal might serve a purpose in the grieving process (e.g., facilitating the process of reviewing life), it contributes to a worsening spiral of isolation and depressed mood in patients who are depressed. While increased social interaction may be beneficial to some patients who are depressed, it is not adequate to resolve depression.

Agitation. Persons who are grieving may be agitated during the early stages but usually respond to support and counseling. Agitation and hyperarousal often diminish or resolve with time. When agitation is present in patients with depression, it may persist without much response to supportive measures.

Active Desire for an Early Death. Many persons who are dying consider the possibility of an early death. Suffering associated with uncontrolled pain, concern about being a burden and a desire to be in control of dying can all result in thoughts of an earlier death. A persistent, active desire for an early death in a patient whose symptomatic and social needs have been reasonably met is suggestive of clinical depression.

Management of Grief

The acronym RELIEVER can serve as a reminder about supportive interventions that can facilitate preparatory grief.

Reflect. Mirror the patient's emotions. Example: If the patient says, "Why did I have to get this horrible disease?" respond with "I can see that you are angry."

Empathize. Try to make a personal connection with the patient. Example: "I can imagine that you are going through rough times. It must be hard not to be able to get out of bed. What can I do to help?"

Lead. Guided questions can help facilitate the grief process. Example: "What concerns do you have about how your loved ones will do after you are gone?" or "When you went through difficult situations in the past, how did you handle them?" Identifying coping strategies that the patient used in the past can be useful so that they can try the strategies that have already been effective for them.

Improvise. Respect the emotional boundaries of patients and offer support within those boundaries. The physician's approach must be tailored to individual patients. What might work with one patient might fail with another. For example, some patients may desire support through talking; others may just want a supportive presence. Some may want time alone; others may cope best by continuing established routines. Patients may suddenly change coping strategies, which requires flexibility on the part of the physician to be able to respond appropriately.

Educate. Explain that grief often comes in waves. Let patients and family members know that people grieve in different ways. It is important to explain that anger experienced by the patients and families toward the self, the situation and others is a common and normal response when facing a terminal illness. Identifying, validating and channeling constructive outlets for anger helps decrease conflicts between patients and their families.

Validate the Experience. Reflect to the patient the normalcy of the experience. Example: "It is okay to cry," or "It seems to me you are responding normally to a very difficult situation."

Recall. Many patients who are dying want to look back over their lives and do a review of their life. Physicians can help by asking about accomplishments, special stories or legacies that patients may wish to hand down to future generations.

Personal

Reflection Exercise #2

The preceding section contained information

about helping caregivers distinguish between preparatory grief and depression. Write three case study examples

regarding how you might use the content of this section in your practice.

Update

Evaluation of a Depression Intervention

in People

with HIV and/or TB in Eswatini Primary Care

Facilities: Implications for Southern Africa

Peer-Reviewed Journal Article References:

Magidson, J. F., Andersen, L. S., Satinsky, E. N., Myers, B., Kagee, A., Anvari, M., & Joska, J. A. (2020). “Too much boredom isn’t a good thing”: Adapting behavioral activation for substance use in a resource-limited South African HIV care setting. Psychotherapy, 57(1), 107–118.

Moitra, E., Tarantino, N., Garnaat, S. L., Pinkston, M. M., Busch, A. M., Weisberg, R. B., Stein, M. D., & Uebelacker, L. A. (2020). Using behavioral psychotherapy techniques to address HIV patients’ pain, depression, and well-being. Psychotherapy, 57(1), 83–89.

Penrose, K., Robertson, M., Nash, D., Harriman, G., & Irvine, M. (2020). Social vulnerabilities and reported discrimination in health care among HIV-positive medical case management clients in New York City. Stigma and Health, 5(2), 179–187.

QUESTION 6

What are eight points of difference between preparatory grief and depression?

To select and enter your answer go to Test.